What should you do with unprofitable customers? What about poor performing employees? Would you allow a quality problem to continue? If your sales were steadily dropping in one market, what actions would you take?

Even though I didn’t give you any data, you probably know the answers to these questions. What you don’t know is which customers are not profitable, which employees have performance issues, where the quality problems are occurring or which markets are losing sales. For those questions, you need data.

Leaders often tell me that they cannot make a decision until they see the data. While it’s true that you can’t complete the decision without the data, you can get pretty far down the path.

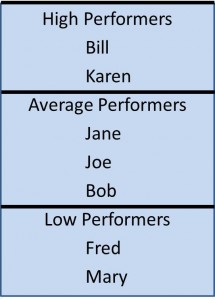

In fact, you’ll probably make better decisions if you think them through prior to seeing the data. For example, consider rating employee performance. Ideally, you should have a set of criteria in mind for what high, average, and low performance look like. Then it’s simply a matter of comparing individual performance against those criteria to get the result. For example you might get something that looks like this:

However, sometimes that’s not what happens. Perhaps we look at the data and see that our up-an-coming superstar, Jane, is third on the list. We “know” that Jane is a high performer. She just had a tougher assignment than Bill or Karen. Certainly if they ran into the challenges that Jane faced, they wouldn’t have done so well. We shouldn’t penalize Jane because we give her the hard tasks, right? All of this might or might not be true, but it’s the conversation that goes on in our head. We decide that our high performer cut-off should come just after Jane, not after Karen as our original criteria might have suggested.

Then, we see Bob. Poor Bob. He really screwed up a couple of years ago and we haven’t forgotten. Sure, he did a pretty good job. Unlike Jane who caught a bad break, he probably just got lucky. We decide to put the low performer cut off just above him. After all, how can we consider a poor performer like Bob to be “average?” The result is a very different picture of your workforce.

Of course, these kinds of decisions are much more subtle. Often they happen unconsciously as our bias takes over the way we view the data and make our decisions. It does happen and not just with performance decisions.

In his book, “The Logic of Failure: Recognizing and Avoiding Error in Complex Situations”, Dietrich Dörner describes similar errors that contributed to the Chernobyl disaster. The team running the reactor (who turned out to be a group of expert scientists) dismissed the data, alarms, and other warnings. Dörner concluded that:

“The Ukrainian reactor operators were an experienced team of highly respected experts who had just won an award for keeping their reactor on the grid for long periods of uninterrupted service. The great self-confidence of this team was doubtless a contributing factor in the accident. They were no longer operating the reactor analytically but rather ‘intuitively.’ They thought they knew what they were dealing with, and they probably also thought themselves beyond the ‘ridiculous’ safety rules devised for tyro reactor operators, not for a team of experienced professionals.”

The people who devised the safety rules based them on a set of criteria based in science. However, when the scientists filtered the real-time data through their personal experience and biases, they decided to move the lines that delineated when corrective action was needed. The result was one of the worst disasters in history.

I’m not suggesting that we completely ignore our experience. However, there are ways to use that experience constructively. Proactively figuring out what actions you’ll take and the criteria for taking those actions reduces the chance of being influenced by your bias. There will be times when, after seeing the data, you might choose to make an exception. However, in that case, at least you are making the exception consciously.

————————–

Brad Kolar is the President of Kolar Associates, a leadership consulting and workforce productivity consulting firm. He can be reached at brad.kolar@kolarassociates.com.