We all have a data footprint. Your data footprint is the amount of data, both relevant and extraneous that you project onto others when you communicate. Traditionally, leaders have had a very large data footprint in their presentations. However, research on how our brain processes information suggests that might be misguided.

Conventional wisdom says that the more data you have the more clear the picture becomes. However, in many cases, more data actually distorts the picture.

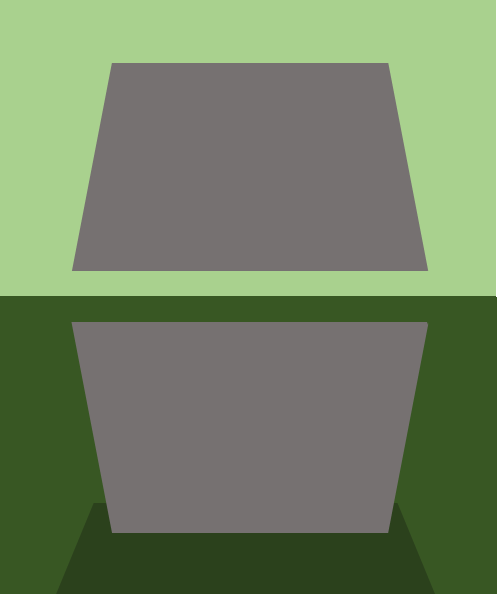

Here is a simple example. The two trapezoids below are clearly the same color.

But look what happens when a small amount of additional data is added.

They are still the same color. Don’t believe it? Just put your finger across the center section. This is a simple example of where extra data distort, rather than clarify, reality.

The unconscious part of our brain processes a lot more information than does the conscious part. It uses all of that information to make sense of what it is perceives.

The unconscious part of our brain processes a lot more information than does the conscious part. It uses all of that information to make sense of what it is perceives.

The addition of the 3D effect on the edges of the trapezoid gave your brain more information with which to work. Your brain thought it was processing a three dimensional image rather than a two dimensional image. It drew upon past experience and brought in additional data about perspective, shadowing, and lighting to make sense of the picture. In doing so, it changed how you consciously perceived the picture. The trapezoids, as taken in by your eye, are the exact same color in both pictures. Your brain changes the color, not your eyes.

Such distortions don’t just happen with visual data. In his book Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely provides an example of “anchoring” – a process by which the brain uses irrelevant data to influence decision making. He asked people to write down the last two digits of their social security number. He then described a bottle of wine. Next, he asked if they would be willing to pay that amount (the last two digits of their social security number) for the wine. Finally, he asked the maximum price they’d pay for the wine. When he compiled the data, it showed a perfect correlation between the last two digits and the maximum price that people would pay. By using the last two digits of the social security number as a comparison, Ariely established an anchor. When making the decision about the maximum amount they’d pay, the participants’ unconscious minds tended toward the anchor. I’ve replicated this experiment in my workshops with over 1,800 people with the same results:

|

Last two digits

|

Average bid

|

|

00-25

|

$47

|

|

26-50

|

$52

|

|

51-75

|

$57

|

|

76-99

|

$66

|

In this case, the anchor didn’t necessarily change people’s perceptions of the wine’s overall value. A person who would pay between $80 and $100 for a bottle of wine, probably isn’t going to go outside of that range. However, the anchor most likely moved them within their individual range. When aggregated across all people, the broader trend emerges.

In other cases, anchors can actually change a person’s perception of value. Ariely asked students which subscription option they’d prefer for The Economist magazine:

On-line only: $59

Print only: $125

Print and on-line: $125

When given these choices, 84% chose “Print and on-line” and 16% chose “On-line only”. Ariely then re-ran the experiment with different students but changed the options:

On-line only: $59

Print and on-line: $125

The “Print and on-line” option that was so popular before only attracted 32% of the students. The “On-line only” option increased to 68%! How can that happen? Why did the students’ perceptions of the value of the different options change so dramatically? The answer lies in anchoring In the first round, the middle choice, “Print only”, created an anchor point. Students didn’t really have a perception of what any of the choices were worth. However, seeing that the “Print only” option had the same cost as “Print and on-line” caused the students to believe they were getting a good deal. When that option was removed the students lost their reference point and made a more value-based choice (as opposed to the emotional choice of getting a good deal).

Anchoring is a common phenomenon often causing us to make irrational decisions. Movie theaters, car dealers, infomercials, and others use it to their advantage to manipulate you into buying or paying more than you should for their products and services. You can’t prevent anchoring from happening but the order in which you present data or the number of reference points you provide can influence what gets used as the anchor.

Sometimes even more subtle and unexpected data affect our unconscious decision making. One study found a strong relationship between the weight of the clipboard upon which a resume was placed and how well recruiters and executives rated that candidate’s credentials. Negotiation studies find that people sitting in hard plastic chairs tend to be less flexible in their negotiations than do those sitting in softer, more comfortable chairs.

Our unconscious brains use a lot more data and information than our conscious brain when making decisions. Because it happens unconsciously, we are unaware of it. We often fool ourselves into believing that we are focused and that our decisions are rational and based solely on relevant data that we have selected. But, as the research shows, there is often more data being used in a decision than we think.

As someone who presents data, your choices play a key role in the amount of extraneous data to which your audience’s unconscious mind is exposed. Start looking critically at your data footprint. Your goal should be to have the smallest data footprint that clearly and honestly tells your story.

One thing that increases your data footprint is including numbers or columns on a table that do not directly influence the decision that you are trying to make or support. Often people copy and paste an entire section of a report into their presentation rather than selectively choosing only the relevant portions.

Another common problem is displaying data in the same manner that it was analyzed. For example, suppose an analysis finds that 18 to 25 year olds spend more money on potato chips than any other age group. The natural tendency would be to replicate your analysis and create a chart showing each age group with their potato chip spend. That’s not necessary. To make the point, only two categories are needed: 18 to 25 and everyone else (the detailed chart can be in included in the appendix). Better, yet, a simple statement that says, “18 to 25 year olds purchase more potato chips than anyone else” is even more streamlined.

A line graph showing weekly sales performance over the course of a year has over 100 data points on it (52 data points showing the date, 52 data points showing the performance on that date, multiple upward and downward spikes, and an overall trend). Remember, to the unconscious mind, everything is data. Any of those data points might be used as your audience’s unconscious minds try to make sense of the graph. The statement, “Sales have trended down over the last year” has only one data point. It’s much harder to unconsciously distort the point.

Less obvious things that increase your data footprint involve non-numeric data that clutter your presentations and reports. Headers, borders, logos, and other widgets on presentation templates add data. Some might be needed to provide clarity (e.g., page numbers). However, a lot of it does not and might be unintentionally influencing people’s perceptions. Perhaps your logo reminds someone of a bad experience they had which is impacting their reaction to your recommendations. Maybe the color palette that you chose was similar to the one used at their wedding (and they have just gone through a bitter divorce).

A final way that we increase our data footprint is by not removing once relevant data. How often do you leave a Powerpoint slide up even though you are no longer focused on the contents of that slide? Do you wallpaper the meeting room with flipchart pages that are no longer the focal point of the discussion? All of these common practices increase your data footprint. Actively manage the information in your environment. If a flipchart page or slide aren’t meant to be the focal point of a conversation, they shouldn’t be seen.

Become mindful of your data footprint. Look at your presentations, reports, and meetings more critically. Assess the amount of extraneous or irrelevant data to which you subject your audience and get rid of it.

Ultimately, you can’t control where someone else is focused or what information his or her unconscious mind uses in making a decision. However, you can minimize some of the choices.

Brad Kolar is an executive consultant, speaker, and author. He can be reached at brad.kolar@kolarassociates.com.